In the 1990s every town had its pop-group, rock-band or DJ that represented them during the rise of Britpop. The South-West was no exception. Bristol had Massive Attack and Portishead, Glastonbury had Reef. Bath had the Propellerheads, and PJ Harvey ascended to global superstardom with her distinctive punk-infused, folk-rock sound. These artists became more than just chart sensations, they waved the flag for local communities and inspired young people to look beyond the pre-internet-era boundaries.

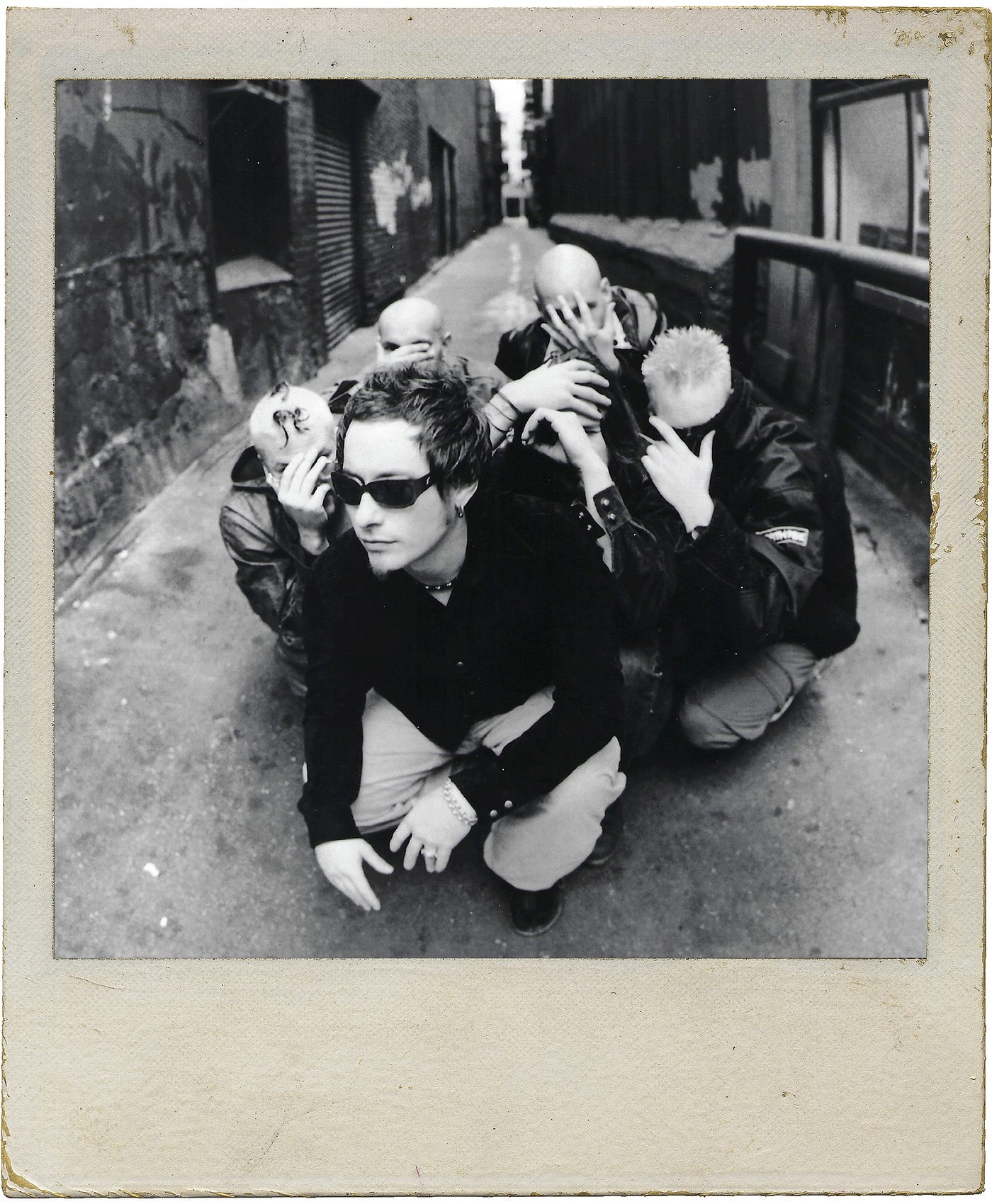

Yeovil was no exception, and in 1995 a group of 20-something-musicians and songwriters met at a pub in Somerton and decided they could take on the world. Ali, Steve, Nigel, Paul, Jim, and eventually Alex created the band that went on to christen themselves Electrasy. They proceeded to have huge chart success both in the U.K, and the U.S with their unique brand of experimental Britpop.

The incredible story of this band is everything other than linear and one-dimensional, which is why it has finally been immortalised in a new fan-led book called ‘Calling All The Dreamers’, tracing the bands early days in Weymouth, Yetminster, Beaminster, Sherborne, and Yeovil, all the way to New York and L.A via studio recordings at the famous Abbey Road, meetings with music royalty such as Clive ‘Arista’ Davis, Sir Robin Millar, and television appearances performing to millions of prime-time viewers.

“Working with the band on this project has been a true labour of love” says author Pete Trainor, “My friends and I were big fans of the band when they were starting out on the Yeovil music circuit, and I knew a bit about some of the stories, but the more I went digging, the more I realised this was a much bigger story that really needed to be shared. It’s so much more than your standard ‘local band gets signed and goes global’ journey. There’s a very good set of reasons very few people remember much about Electrasy other than one top-20 hit single; It’s because they were buried by the industry that had plucked them from humble roots, and I needed to find out why.”

This has been an itch I’ve been trying to scratch for over 15 years, and we finally got to tell the story. It’s been magical. Pete Trainor

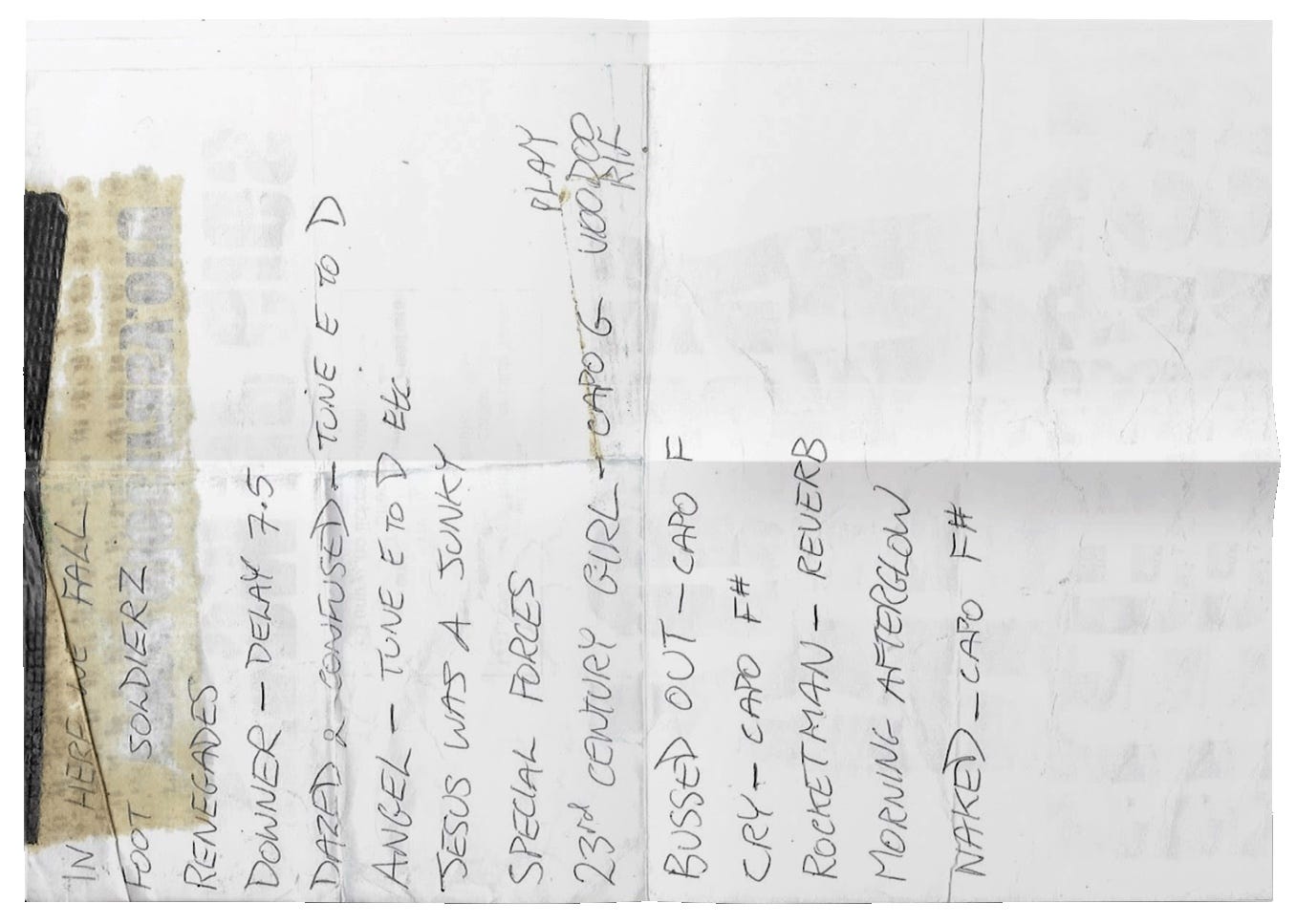

Electrasy’s first album, ‘Beautiful Insane,’ had its early demos and production supported by local producer Jon Sweet in his garage studio, and a lot of the additional work was recorded at the former Small World Studios in Yeovil. Throughout 1996, 1997 and 1998 dozens of gigs at venues like Gardens, The Ski Lodge, Yeovil Snooker Club, The Forresters Arms and The Quicksilver Mail created a dedicated fanbase, and the album went on to sell 60,000 copies in the first few months after its release, putting the band and Yeovil on the music map in a way that few thought possible. Championed by Chris Evans, Jo Wiley, and the U.K music press, the band seemed unstoppable, and even after their first record contract with UMG was terminated unexpectedly the band still played the coveted sunset spot at the second stage of Glastonbury Festival in 1999.

“We definitely felt like we were ready to take on the world when Arista took us over to America,” says singer Ali McKinnell in the book. “We had one of the best song-writers of a generation in Nigel, and the rest of us were damn good at what we were doing. But the industry often has different ideas, and when music piracy took hold at the same time as our rise we found ourselves constantly being somewhere between high and low. It was a very difficult journey in parts.”

The book looks at multiple angles of the band’s story, from the impact they had on local youth culture and economy, all the way to the advent and subsequent destruction digital caused the industry as a whole.

Guitarist Steve Atkins is quick to remind people of the opportunity but harm digital brought to bands who grew up analog, but entered digital; “One stream of a song on YouTube earns us £0.00053. A stream on Spotify is £0.0034 and AppleMusic is £0.0057. To put that into context for you, if we had one million streams on YouTube we’d make £533 or £3380 on Spotify. Bands can’t make enough to support themselves, let alone a tour, so we literally can’t get out on the road as much as we want. It’s a very dark pattern.”

Which leads to the final part of the book taking a look at the venues that first supported the music scene in the area. All boarded up, bulldozed, or turned into flats, towns like Yeovil are now devoid of the local music scene that inspired so many to see the world differently, and break away from crime or substance abuses.

“I definitely wasn’t expecting to find what we found,” says Pete. “When I came back to Yeovil to retrace the steps of the band I had no idea it was all gone. Even the studios where they recorded have shut and been sold off. The music ecosystem is very symbiotic you see – Bands need venues to play in, and studios to record in. Venues and studios need bands from the local area to bring their fanbase in to fill the tills.”

‘Calling All The Dreamers – The story of a local Britpop band who went to space and back’ is available now on Amazon. All proceeds from the book will be used to fund a tour of local venues in 2024. The band also release their brand new, home-grown album called ‘To The Other Side’ in July 2023, which music lovers can buy from BandCamp.

Recent Comments